Kidney cancer accounts for 2-3% of all cancers and 95% of cancerous growths of the kidney. It is more common in people between 60 and 70 years of age, although sometimes it is seen in younger patients.

Nearly 30% of patients with kidney cancer have spread of the disease elsewhere at the time of being seen by their doctor. Recurrence rates vary between 5 to 30% and is likely to happen within the first 6 years. Computerised tomography (CT) scans are done over this period of time to rule out recurrences. Kidney cancer could be hereditary or non-hereditary. When a patient with localised kidney cancer is treated surgically, 5- and 10-year disease-specific survival can approach 95%.

Types of Kidney Cancer

The most common form of kidney cancer is renal cell carcinoma (RCC). RCC is two times more common in men than in women. Higher rates of renal cancer are reported from central European and Scandinavian countries. The kidney tumour may remain silent for a period. In its early phase, the tumour is usually detected by scanning (Ultrasound, for example) or tests (such as CT or MRI) for some other problem in the abdomen. There has been an increase in the number of cases due to their early detection during imaging investigations for other reasons.

The behaviour and course of RCC varies from patient to patient. A small proportion of patients tend to do well irrespective of treatment they receive. RCC is resistant to conventional chemotherapy and radiotherapy. However, there are some advances in the kidney cancer treatment by using newer drugs that have action on the growth of cancer cells.

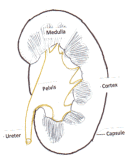

There is another type of growth arising from the lining of the urine-collecting part of the kidney (pelvis) called transitional cell carcinoma of the pelvis/ureter (see Figure 2). This is similar to the tumours that comes up in the bladder.

Types of Renal Cell Carcinoma

RCC arises from mature kidney elements, namely from parts of the nephron, a blood filtering unit. The main feature of RCC is its ability to make new blood vessels (angiogenesis). It is difficult to understand the details of various types of cancers that are mentioned below.’

Clear Cell RCC

This type accounts for 75% of tumours. Usually they are single, solid and large size (few mm to 20cm) tumours. The cells show clear cytoplasm and cell wall and are arranged as sheets of cells. In some clear cell tumours, there may be cluster of cysts (multi-locular cystic RCC).

Papillary RCC (PRCC)

This accounts for 5-10% of kidney tumours. They present a discrete mass with variable size and could occur in more than one site (multi-focal). The prognosis of PRCC is more favourable than clear cell RCC. Tumours have a tubular architecture without any clear cells.

Chromophobe RCC

This type of RCC accounts for 5-10% of cases. Tumours are discrete and solitary. The cells have irregular nuclei with no staining around them.

Collecting Duct RCC

This is a rare type of tumour seen in less than 1% of cases. It arises from the ‘collecting duct’ of the nephrons.

Medullary Carcinoma

This is again a rare tumour and only recognised very recently. It arises from the medulla. This tumour is generally seen in patients of Afro-Caribbean descent. All patients reported with this type have a sickle cell trait. Under the microscope, tumours look similar to those from Collecting Duct RCC.

Kidney Cancer: Possible Causes and Risk Factors

Although the exact cause of RCC is not known, a number of risk factors, including lifestyle and environmental risk factors, have been associated with the development of kidney cancer.

Cigarette Smoking

This increases the risk of developing RCC. It is related to smoking duration and severity in both men and women. Stopping smoking decreases risk with the years but this is mainly evident after stopping for 20 years.

Diet and Obesity

There is an association between excess weight and kidney cancer, particularly in women. Nearly 30% of the cases with RCC are weight-related.

High Blood Pressure

There is some evidence that high blood pressure plays a role in the development of RCC. There may be risks associated with drugs used for the treatment of blood pressure.

Drugs and Toxic Agents

Such as lead, arsenic and cadmium. Cadmium may also increase the cancer-causing effect of smoking.

Dialysis

Men and women undergoing dialysis tend to develop a condition where cysts develop in the kidneys. These cysts can develop RCC.

Occupation

Several studies indicate that the risk of developing kidney cancer may be higher than average among people with certain jobs. Increased risk has been seen in coke oven workers and those who work with asbestos. Similarly, exposure to tetrachloroethylene (a dry cleaning solvent) and to trichloroethylene (used in metal degreasing) may be associated with kidney cancer.

Exposure to Radiation

Radiotherapy treatment for other cancers (e.g. testis cancer) may expose the kidney to radiation and cause kidney cancer at a later date.

Genetic and Hereditary

It is estimated that nearly 60% of RCC diagnoses are related to genetic factors as shown in a study done in Iceland. Hereditary cancers account for less than 5-10% of renal tumours.

Medications

There was a drug called phenacetin for pain relief which is no longer available in the UK or USA. This drug was linked to RCC.

Hereditary Tumours

These tumours are passed from the parent to the offspring through genes.

von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) Disease

This is a rare type but well known of the familial cancers. The condition is due to a defective gene called VHL, which predisposes a person to a variety of malignant and benign neoplasms, most frequently retinal (eye), cerebellar (brain), and spinal haemangioblastoma, RCC (clear cell type), phaeochromocytoma and pancreatic tumours.

Hereditary papillary renal carcinoma (HPRCC)

This type of RCC is of papillary type, which is multifocal and occurs in both kidneys. It has a favourable prognosis and occurs at a later age.

Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome

Inherited predisposition to develop benign tumours of the hair follicle, predominantly on the face, neck, and upper trunk, and are at risk of developing renal tumours, colonic polyps or tumours, and cysts in lungs.

Hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell carcinoma (HLRCC)

Skin nodules called leiomyomata found mainly on the arms, legs, chest, and back. Women with HLRCC often develop uterine fibroids known as leiomyomas, or, less commonly, leiomyosarcoma (malignant form). People with HLRCC have about a 20% risk of developing papillary renal cell carcinoma.

Succinate dehydrogenase B (SDHB) associated renal cancer

Heritable paraganglioma and familial clear cell RCC are rare forms of clear cell RCC. Hyperparathyroidism-jaw tumour and papillary thyroid carcinoma are associated with papillary RCC.

Tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC)

TSC is a genetic condition associated with changes in the skin, brain, kidneys, and heart. People with TSC have about a 4% risk of developing kidney cancer. TSC is caused by a mutation on either the TSC1 or the TSC2 gene. Approximately 60% of people with TSC do not have a family history of the condition.

Other tumours that may mimic renal cancer: In addition to renal cancer, small tumours of the kidney could be due to benign conditions such as oncocytoma, angiomyolipoma, a complex cyst, or a hypertrophied column of Bertin. Radiological examinations can diagnose all these conditions. Oncocytoma is a benign swelling accounting for 3-7% of all renal tumours. It may produce RCC symptoms like bleeding and pain.

Fuhrman Grading

Most cancers have a grading system reflecting prognosis. Fuhrman grading is on a scale of 1-4, where grade 1 carries the best prognosis and grade 4 the worst. It takes into account the characteristic features of the nucleus of the cells.

Kidney Cancer Symptoms

There are often no obvious symptoms at the start of renal cancer growth. As mentioned earlier, kidney cancer is being picked up more often on ultrasound scans and sometimes on other scans (e.g. CT or MRI) that are done for other reasons. So they are being found at an earlier stage. Once the cancer begins to grow inside the kidney, the kidney disease symptoms can become more obvious.

There may be following symptoms present in cases of kidney cancer:

- Blood in the urine

- A lump (mass) in the stomach area

- High blood pressure

- High temperature

- Anaemia

- Weight loss/tiredness

- Loss of appetite

- Fever

- Raised blood calcium levels

- Abnormal liver tests

Kidney Cancer Tests

Physical examination, including blood pressure tests, is to check the state of general health. The following tests may be necessary in addition to doctor’s physical examination for diagnosing kidney cancer:

Blood Chemistry

Blood chemistry tests measures substances like creatinine, urea and electrolytes in the blood, which are cleared by the kidneys. Normal levels would indicate normal kidney functioning.

Urine Examination

A test to check the colour of urine and its contents, such as sugar, protein, red blood cells, and white blood cells.

Liver Function Tests

A sample of blood is checked to measure the amounts of enzymes released by the liver. An abnormal amount of liver enzymes can be a sign that cancer has spread to the liver. Certain conditions that are not cancer may also increase liver enzyme levels.

Ultrasound

A procedure in which high-energy sound waves (ultrasound) are bounced off internal tissues or organs and make echoes. The echoes form a picture of body tissues called a sonogram. The examination will show the location and size of the tumour if present.

CT Urography

A series of pictures of the kidneys, ureters, and bladder to find out if cancer is present in these organs. A contrast dye is injected into a vein. As the contrast dye moves through the kidneys, ureters, and bladder, the radiology doctor carefully examines for any abnormality.

MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging)

A procedure that uses a magnet, radio waves, and a computer to make a series of pictures of areas inside the body. It is particularly useful in studying blood vessel involvement.

MAG-3 (Mercaptuacetyltriglycine) Renography

A renal MAG3 scan is a nuclear medicine test that allows doctors to see your kidneys and learn more about how they are individually functioning (split function). This is particularly useful in hereditary cancers, as tumours are often small and can be numerous.

Biopsy

The removal of cells or tissues, which are viewed under a microscope by a pathologist to check for evidence and signs of cancer. To do a biopsy for renal cell cancer, a thin needle is inserted into the tumour and a sample of tissue is withdrawn. In most cases, however, biopsy is not performed as the scan appearances are sufficient to make a diagnosis of kidney cancer. In some cases, when the tumour has spread, it may be necessary to do the biopsy prior to drug/non-surgical treatment.

Stages of Kidney Cancer

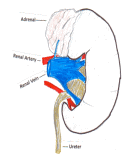

Once a diagnosis of RCC is made, correct staging of the tumour is the next step. This is done by looking at all the tests done. In the staging process, the doctor assesses the limits of the tumour-local extent and whether it has gone outside the kidney. This is done with CT scanning. In recent times, due to advances in tests used in staging and improvements in surgical techniques, in some cases it has become possible to remove or destroy the tumour and save the kidney (minimally invasive treatments).

TNM Classification System for Kidney Cancer

The tumour, nodes, and metastases (TNM) classification is commonly used for staging. The major advantage of the TNM system is that it clearly differentiates between different types of spread. Here are the classifications the TNM system uses:

Primary kidney tumour (T)

TX – Primary tumour cannot be assessed

T0 – No evidence of primary tumour

T1 – Size of tumour ≤7 cm limited to the kidney

T2 – Size of the tumour ≥7 cm in greatest dimension, limited to the kidney

T3 – Tumour extends into major veins or adrenal gland or tissues surrounding the kidney (fat) but not beyond the Gerota fascia (Outer fibrous sheath outside the fat)

T3a – Tumour invades adrenal gland or perinephric tissues but not beyond the Gerota fascia

T3b – Tumour grossly extends into the renal vein(s) or vena cava below the diaphragm

T3c – Tumour grossly extends into the renal vein(s) or vena cava above the diaphragm

T4 – Tumour invading beyond the Gerota fascia

Regional lymph nodes (N)

NX – Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed

N0 – No regional lymph node metastasis

N1 – Metastasis in a single regional lymph node

N2 – Metastasis in more than 1 regional lymph node

Distant metastasis (M)

MX – Distant metastasis (spread) cannot be assessed

M0 – No distant metastasis

M1 – Distant metastasis

Spread (Metastasis) of RCC

Cancer cells break away from the primary (original) tumour and travel through the lymph or blood to other places in the body forming another (secondary) tumour. This process is called metastasis. There are three ways by which RCC spreads. They include:

a. through the tissues around the kidney

b. through Lymphatics

c. blood vessels

Kidney Cancer Treatments

The treatment options for renal cell cancer are surgical removal, chemotherapy, hormonal therapy, immunotherapy, or combinations of these. Surgical removal remains the only known effective treatment for localised RCC. Surgical treatment (removal of the diseased kidney) is also sometimes used for palliation when the disease has spread outside the kidney (metastatic disease). Once a diagnosis is made the treatment is planned by urologist and oncologist depending on the staging of the RCC.

Types of Kidney Cancer Treatment

The types of treatment for kidney cancer include:

Active Surveillance

Not treating RCC at all in selected cases has been recognised only in recent times. The practice of watching RCC is contrary to the conventional treatment of RCC or any cancer for that matter. In patients with small tumours, when the features are difficult to determine, it may be safer to watch over a period of time to see the rate of growth and other features. Patients who are not fit for any form of treatment are also suitable for surveillance.

Radical Nephrectomy

In this operation, the whole kidney is removed, along with its surrounding structures (fat, fascia and related lymph nodes). In some cases, the adrenal gland is also removed. This is done either by keyhole surgery (depending on the size) or by an open operation. In laparoscopic/robotic surgery, ports (‘key holes’) are created through which instruments are inserted. The procedure is performed with the help of a camera that shows the inside of the abdomen on a video screen. Keyhole procedures are done only by specially trained surgeons. Occasionally keyhole operation may have to be converted to an open technique because of problems arising during surgery.

Open Radical Nephrectomy

This was a standard operation for many decades until the advent of laparoscopic (keyhole) surgery in the 1990s. It is still used for large kidney tumours or when the cancer has spread to the veins. The kidney can be approached by opening the abdomen through a cut in the middle (midline incision) or across below the rib cage (subcostal incision). A surgeon can also approach the kidney from the back below the rib cage. Recovery takes longer than for a keyhole operation. In addition, there will be a larger scar on the abdomen and the wound may be more painful.

Partial Nephrectomy

In this operation, only the tumour is removed, leaving the kidney in its place. This is also called nephron saving surgery (NSS). NSS is generally contraindicated in the presence of an obvious spread of the cancer. This operation can be performed either by keyhole or open operation depending on the size and site of the tumour. Tumours measuring less than 4cm are ideal for NSS.

Over the last decade or so, NSS restricted to tumours in patients with a solitary kidney or those with decreased renal function has become an accepted alternative to radical nephrectomy, even for patients with both kidneys intact. With modern advances in control of bleeding, the operation has become more feasible.

Minimally Invasive Kidney Cancer Treatments

Cryosurgery: Kidney tumours can also be treated with cryoablation by placing one or more fine needles into the tumour. It is then cooled to temperatures below –40º C. This causes ice formation inside the cancer cells leading to their death. The procedure can be carried out either through a traditional open operation or by key-hole (laparoscopy) method or under CT/MRI guidance. Early results are promising but failures are treated with standard operation.

Radiofrequency ablation (RFA): It is a minimally invasive treatment for RCC. A probe that is guided into the tumour through CT or MRI heats and destroys cancer cells.

High-frequency electrical currents are then passed through the electrode, creating heat that destroys the abnormal cells. Tumours that are less than 4cm are selected for this type of treatment.

Extracorporeal high-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU): In this technique sound waves pass through biological tissues and gets absorbed. The mechanical energy is converted into heat energy that damages the cancer cells. This technique needs more studies and research.

Therapeutic results are still being studied and from clinical point of view, these treatments must be considered as techniques under investigation at present time. Further research is needed to settle its real indications in the management of small renal masses.

Recurrence Risks of Kidney Cancer

Once the kidney is removed, an assessment is done to determine the chances of future recurrence. This is done by CT scans.

Risk Factors for Recurrence

- Tumours involving capsule and the fat around the kidney

- Lymph node involvement at the time of diagnosis

- High Fuhrman grading (the grade is based on nuclear size and shape and the prominence of nucleoli)

- Sarcomatoid nature of the tumour (the word sarcomatoid indicates the microscopic appearance of a specific type of renal cancer, which shows highly pleomorphic spindle cells and/or giant cells resembling sarcoma: a tumour of connective tissues, along with a varying degree of clear or granular epithelial cells that are seen in RCC. It is an uncommon renal malignancy, with a reported incidence of 0.7% to 13.2% of all RCCs)

- Involvement of blood vessels

- Adrenal gland involvement

- Tumour necrosis

Risk of Recurrence in the Opposite Kidney

This is a very common question asked by patients. Sometimes tumours can be seen in both kidneys at the same time and they are detected at the time of first assessment. Some tumours may appear in the opposite kidney after a period of time. This could be a spread from the kidney that was removed previously or a new tumour in the otherwise normal kidney.

Metastatic RCC

Although the majority of patients present with a localised tumour, in almost half of these patients the disease may spread. In nearly a third of patients, spreading is evident at the initial assessment. When cancer cells spread outside the kidney, treating the local tumour by removing the kidney is not usually effective. The only way of reaching dispersed cancer cells is by chemotherapy or by sensitising the body against the RCC (immunotherapy). Traditional chemotherapy has shown negligible response rates. However, a number of new drugs have shown promising results.

Immunotherapy

Individual case reports have suggested spontaneous disappearance of tumours indicating immune responses in RCC. This has lead to the introduction of cytokine therapy (immunotherapy). Cytokines are a number of small proteins released by specific cells that carry signals locally between cells, and thus have an effect on the behaviour of other cells. Cytokines act as intercellular mediators in the generation of an immune response. The cytokines include the interleukins, lymphokines and cell signal molecules, such as tumour necrosis factor and the interferons, which trigger inflammation and respond to infections. The most widely used cytokines in metastatic RCC are interferon-α (IFN-α) and interleukin-2 (IL-2) with response rates of 10-20%. Some patients may even achieve long-lasting remission, especially with a high dose of IL-2. It is important to note that in some patients, the treatment may be poorly tolerated with very little anti-cancer activity.

Signal Transduction Inhibitors

Signal transduction in cancer cells is a complex process. Like normal cells, cancer cells use signalling for their growth, development and survival, which is mainly in the form of chemicals. They usually stick to one pathway (‘oncogene addiction’) for survival. Highly selective or specific blocking of the pathway can result in major treatment response and survival. Signal transduction usually involves receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) that activate kinases in the cells. Some of the signal transduction inhibitor drugs that are used in metastatic kidney cancer include sunitinib, sorafenib, temsirolimus, pazopanib, axitunib, valatinib, and lapatinib, either as single agents or in combination. Most of the agents are used in trial setting so the oncologist discusses plans with the patient before planning any treatment.

Surveillance after Surgery

Once the surgical operation is done, attention is diverted to recovery and future assessments to see the progress of the treatment. This is called surveillance. In first couple of weeks, the surgeon would like to know whether there are any complications of surgery. After 6-9 months surveillance is done to see whether there are any late complications or recurrence of the cancer. In addition, the function of the remaining kidney is assessed. The surveillance therefore includes blood tests, ultrasound and CT scans. Examination of chest is also included to make sure that tumour has not spread to the chest.

Kidney Cancer: Frequently Asked Questions

Where does kidney cancer spread to first?

After the initial tumour that grows in the kidney, the next area it is possible to spread to can be nearby blood vessels, a lymph node, adrenal gland, or the fat that surrounds the kidney.

How fast does kidney cancer spread?

Kidney Cancer can spread most in its early stages, where it is also most undetectable. The growth of cancerous cells past this stage can depend on a variety of factors including age, sex, health, diet and genetic history. If in doubt, it is always better to get a test from a professional.

How long does cancer take to develop?

Kidney cancer develops in different timeframes, dependant on a variety of factors. RCC comes in these four different stages:

Stage I: Minimal Cancer cells found around the kidney

Stage II: Cancerous tissue has developed in the kidney, but this has not affected the bloodstream

Stage III: Cancer has spread from the kidney into the blood and lymph nodes

Stage IV: Cancer Has spread to other body parts (it has become metastatic)

What is the kidney cancer recurrence rate?

This will vary from person to person. Post-treatment in the UK, it is normal to have follow up appointments for up to 5 years. This is to check if any cancer has reappeared in the body so it can be treated early.

The frequency of these appointments will vary depending on your recurrence risk factor. Steps you can take for yourself to help minimise recurrence are:

- Maintaining a healthy diet containing fresh fruit, vegetables and fish

- Try to learn to relax with techniques such as meditation, or minimising other stressful areas in your life

- Try to stop smoking and cut back on drinking excessive amounts of alcohol

Is a biopsy necessary?

A surgeon performs a kidney biopsy with a specialised needle called a tru-cut needle. However, it has a limited role in diagnosis due to advanced imaging techniques like CT scans. In addition, biopsy may fail to give a diagnosis and has higher false negative rates. There is also a possibility of complications with renal mass biopsy. In modern practice, surgeons perform a biopsy in patients who have spread of the disease (metastatic cancer) or when surgical treatment is not possible. It is also indicated if imaging study findings indicate benign tumours of the kidney so that unnecessary operation could be avoided.

How long it takes to recover from surgery?

I send patients home within 2-3 days after keyhole surgery and 4-5 days after open surgery. Although keyhole operations look quite trivial from the outside, the intensity and extent of surgery is similar to an open technique. I advise patients to take it easy for at least four weeks. Doctors give all patients anticoagulation for at lest 2-3 weeks after the operation to prevent deep vein thrombosis. All sutures are inside so there is no need to go to a GP surgery or come back to the hospital for removal. Professionals can remove dressings 48 hours after the operation and encourage patients to have a shower, making sure that no rubbing of the wound occurs. A review assessment takes place after 4 weeks to make sure that everything is going well and to discuss the results of the laboratory examination of the kidney and tumour.

How long does it take to do a nephrectomy operation?

This is a question patients commonly ask. I tell them that this can be highly variable – anything between 2-4 hours. The anaesthesia itself can take up to 30 minutes and positioning prior to the operation takes another 15-20 minutes. As modern anaesthesia is safe there is no need to hurry up the procedure as safety and correct surgical steps are the most important aspects of the operation.

What are the possible complications of a nephrectomy?

As blood vessels to the kidney carry a considerable amount of blood, bleeding from these vessels can be considerable amount. In addition, there will lots of abnormal vasculature around the tumour with thin-walled blood vessels. These can easily bleed. Average blood loss with keyhole surgery may be as little as 50-100mls. There will be some blood loss with removal of the kidney because of blood trapped inside the kidney. This may vary between 300-700mls.

Generally I do not find it necessary to give a blood transfusion. However, there are instances where blood loss is inevitable, particularly when the tumour has entered bigger vessels (for example when a big abdominal vein like the inferior vena cava has a tumour inside).

How many weeks of rest do I need before I can go back to work?

When doctors mention the word ‘rest’, this is not same as the bed rest. You are expected to be active in your home surroundings – making a cup of tea, light dinner, fetching a newspaper from the corner shop, driving to your supermarket (less than 6-7 miles). Swimming and walking are good exercises for adapting gradually. Make sure you stick to a healthy diet and drink a lot of fluids.

Is there anything I can do to prevent the cancer coming back again?

Your doctor/oncologist will take care of the tests and follow up for a period of at least 5 years. Review clinic appointments are important to get all the information about your current medical condition. However, there are certain things you can do to improve your health and chances of prevention of the cancer coming back again. If you are obese, get good professional medical advice to lose weight. If you are a smoker, make every effort to give it up and similarly drink alcohol in moderation. Go for a healthy balanced diet, avoiding oily food and animal fats.

REFERENCES

Linehan WM. Genetic basis of bilateral renal cancer: Implications for evaluation and management. J Clin Oncol 2009; 27(23): 3731-3

Scatarige J C, Sheth S, Corl F M, Fishman E K. Patterns of Recurrence in Renal Cell Carcinoma-Manifestations on Helical CT. AJR 2001; 177:653-8

Richard A, Lidereau R, Giraud S. The growing family of hereditary renal cell carcinoma. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2004; 19(12): 2954-8

Useful Websites for Kidney Cancer

National Cancer Institute: www.cancer.gov

Cancer Research UK: www.cancerresearchuk.org

Mr Vinod Nargund is a Consultant Urological Surgeon specialising in Urological cancer, male sexual and fertility problems. He was trained in Urology at the City Hospital Belfast, the Royal Infirmary Bradford and the Churchill and John Radcliffe Hospitals in Oxford. You can view all of his qualifications on his biography page.